by Gabriela Geselowitz

by Gabriela Geselowitz

Most people who have heard of Marie Dressler know her for her monumental acting career, spanning the stage to silent films to talkies, including an Oscar for Best Actress. (A Google Doodle even ran in 2020 in her honor!) Her career went through booms and busts, but she remained a beloved celebrity for decades. However, there is more to her story often left out: her activism. She did not dedicate her entire life to political causes, but crucial moments came when she leveraged her star power for the greater good. This was most evident when she played a vital part in labor history, organizing the Chorus Equity Association amid Actors' Equity Association's first strike in 1919.Dressler was born Leila Marie Koerber in Ontario, and her family immigrated to the United States when she was a child. At age 14, she left home to pursue her acting career, claiming she was 18 and choosing the stage name Marie Dressler.

Dressler began in the chorus, mostly touring the Midwest earning $8 a week, roughly $200 to $250 in today's money. Dressler considered it a decent sum for her time and place, and she would send half home to her mother. As someone without a formal education, Dressler found her time in the chorus incredibly valuable, but it was grueling and unpredictable. Sudden changes in schedule, derelict hotels and withheld pay were all common, to say nothing of then-standard industry practices like being responsible for one's own costume or rehearsing two shows at once while performing a third.

A gifted comedian, a strong singer and a diligent worker, Dressler moved towards bigger theaters and higher-paying jobs. By the time she made her Broadway debut in 1892 in The Robber of the Rhine, she was making $50 a week – enough to support herself and her family. Within years, her Broadway roles were starring ones, most notably the title character in Tillie's Nightmare in 1910.

Dressler was outspoken offstage as well as on, and while she held strong political views, they evolved over time. For example, in the early 1910s she was against women's suffrage, insisting, "I am a staunch believer in woman's equality with man, but I believe it is a mental equality, not a physical one, and that womankind was never devised to steer the ship of state or to go to the polls and cast the ballot with the men." By 1915, perhaps because of close relationships with prominent New York suffragists, she had changed her mind. She made impassioned speeches in favor of women's suffrage, and according to one story, she wagered golf games with men on their support for the cause – and defeated ten of them.

Portrait of Marie Dressler from the 1906 edition of Who's Who on the Stage.

In 1914, Dressler made history when she went out west to California to star in the film adaptation of Tillie's Nightmare, Tillie's Punctured Romance, the first feature-length comedy movie. Also starring in the movie were Mabel Normand and Charlie Chaplin. (Where's Marie's Broadway bio-musical!?)

The film was a hit, but after a few years in Hollywood, her film career stalled. For a time, she found another calling: supporting the United States in World War I. She parlayed her performance skills into making speeches urging ordinary Americans to buy war bonds, sometimes speaking extemporaneously. Here, on a much larger scale, she synthesized her celebrity and her ability to entertain into the power to rally a large crowd into action.

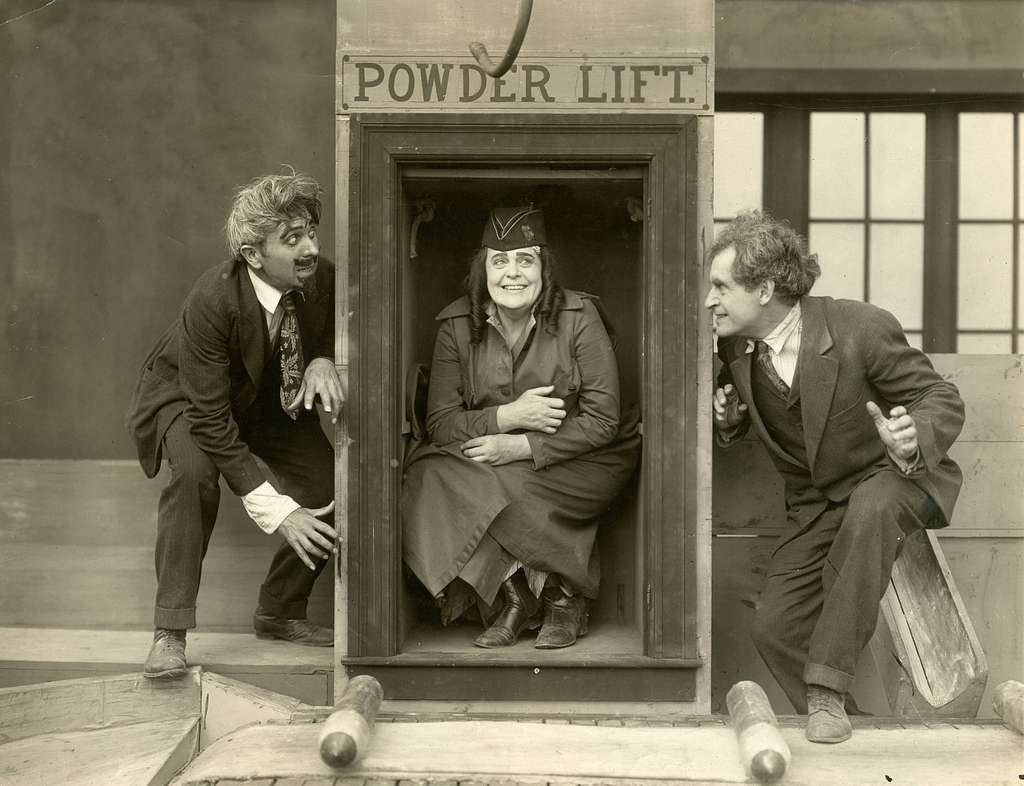

A publicity image for Tillie the Scrub Lady, a 1917 film produced by and starring Marie Dressler and distributed by Goldwyn Pictures. It's one of four films in which Dressler portrayed the character of Tillie.

Following the war, Dressler's career stagnated again, but she rallied as always and spent much of her time donating her performances, in venues ranging from hospital wards for wounded soldiers to large houses to fundraise for the American Red Cross.

In the meantime, Actors' Equity Association was just getting on its feet. Although the union was founded 1913, those first few years it struggled to gain a foothold in the industry, with many employers refusing to recognize Equity or honor the early contract. Then, in 1919, when the new Producing Managers' Association refused to negotiate with Equity, the union's work accelerated. Well over 1,000 new members joined the union, Equity joined the American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L., now the AFL-CIO), and shows began to shut down as companies joined the country's first major theatre strike.

Equity was not the first attempt at unionizing the theatre, but early attempts were not only less effective, but more exclusionary. The White Rats of America, for example, which organized vaudeville performers, only accepted white men as members. Equity was more inclusive from the beginning, and some of its early activists included women at a time when the Nineteenth Amendment had not even yet been fully adopted.

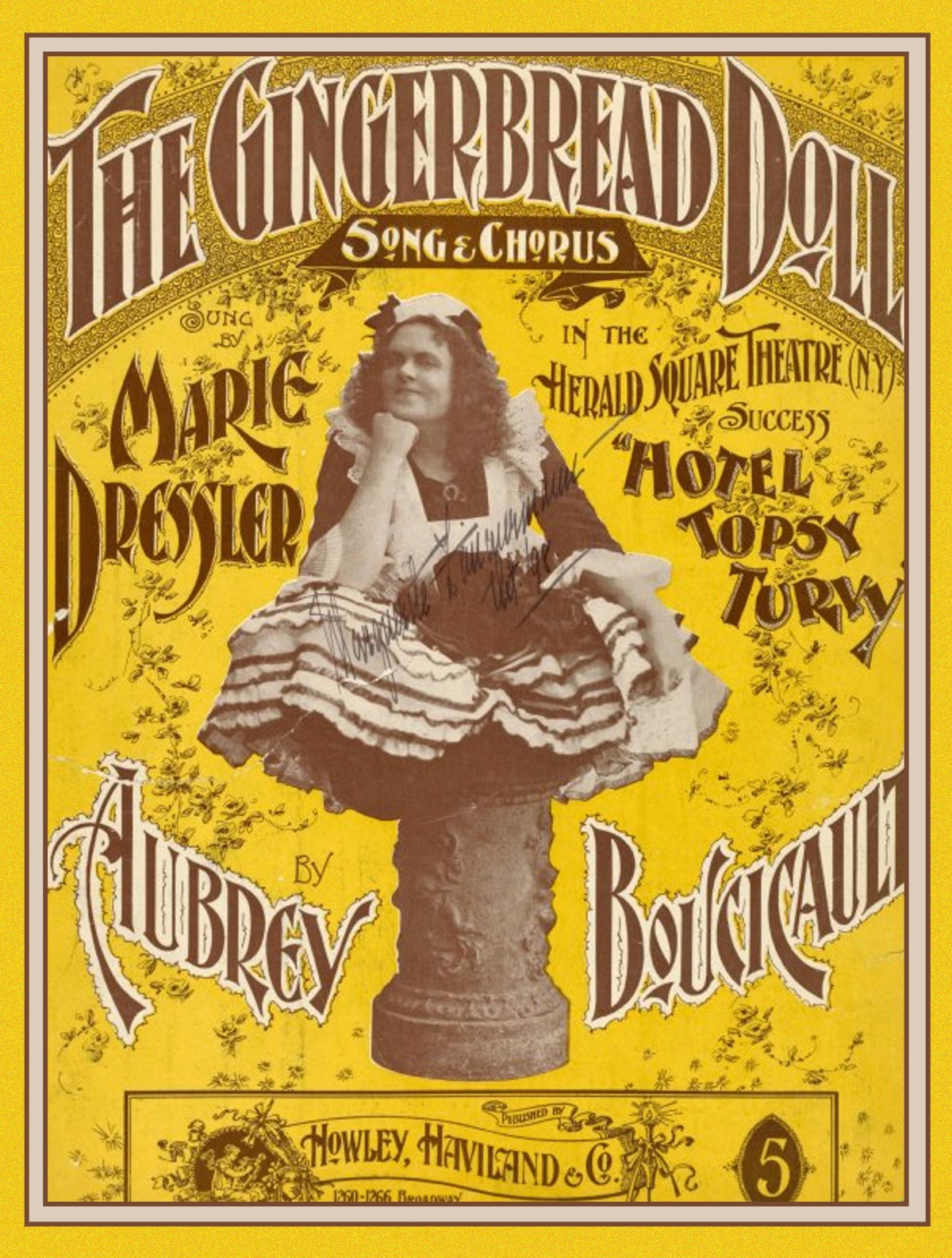

Marie Dressler is featured on the sheet music cover for "The Gingerbread Doll," a song she performed in Hotel Topsy Turvy at the Herald Square Theatre, 1898.

However, the makeup of the union reflected, and sometimes perpetuated, social inequities. For example, Equity did not have any Black members at the time of the strike; the first Black member joined the following year, in 1920. Furthermore, chorus members did not qualify to join. Notably, while chorus work was not exclusively performed by women, it was overwhelmingly associated with "girls," with many in the industry even referring to them as "ponies."

Stereotypes of the chorus girl also persisted: She was more beautiful than talented, hired more to serve as set dressing rather than perform skilled work. She was likely using the job to try to be visible to rich men. The chorus had connotations of frivolity.

Once the strike was underway, solidarity from other theatre workers was indispensable; IATSE and the AFM, for example, swiftly voiced their support. Employers began to eye the chorus as an opportunity to undermine their fellow performers and tried to create the narrative (not without some merit) that Equity had abandoned the less privileged workers. Many chorus members had already walked out in solidarity with their principals, but the ranks were divided.

Dressler was not an Equity member herself, but she saw the importance of the strike. ("I never could keep out of a good fight," she wrote.) Crucially, she saw value of the chorus in that moment.

Dressler had never forgotten the chorus. As early as 1901 she had leveraged her star power to pressure producers to improve their working conditions. Furthermore, she had always made it a point to socialize with the chorus, and she had earned a reputation with these workers for being generous. Now, she knew it was time to make use of that trust. On August 12, 1919, she presided over a meeting of chorus workers at the New Amsterdam Theatre, urging them to formally organize. The evening reached a climax when fifty chorus actors from the Hippodrome, which had not been an Equity organizing target, marched two by two into the meeting. The assembled crowd of hundreds formed the Chorus Equity Association of America.

The jubilant crowd unanimously elected Dressler as its first president, despite her protestations of being old and long out of the chorus. Productions each put forth one male and one female chorus member as their representatives. Lillian Russell, theatre star and a close friend of Dressler, donated $100,000 to help launch the union. Ethel Barrymore had stopped by to see what all the excitement was and made an impromptu speech of support.

Dressler called herself "General of the Chorus Amazons," a martial expression for a time of struggle, but still one with distinctly female connotations. The demands Dressler soon issued on their behalf were ambitious, covering everything from salary to scheduling to sleeping accommodations on trains, many of the problems she had encountered as a young actor.

Dressler occupied an interesting position in the strike as someone who did not stand to benefit from its outcome, especially as far as the chorus was concerned. Nor did she consider the chorus a permanent profession; she saw it as a "training school, an apprenticeship for bigger work," as she had used it, seeing principal roles as a step forward.

She also stated that if the women of the chorus did not have the means and protections to take care of themselves, they would be at risk of being "obliged" to go into sex work, asserting that producers could and did blackmail chorus actors for everything from attempting to move to a principal role to refusing their romantic advances. She recast the "chorus girl" not as a gold-digger, but a potential victim.

Dressler saw the employers as the impediment to a healthier theatre industry, and she saw unionizing as a way of implementing a system that would benefit everybody:

"No More Pay, Just Fair Play": Marie Dressler (center) and Ethel Barrymore (far right) on the picket line during the 1919 strike.

"I'm hoping to God that this struggle will be the means of bringing the managers and actors nearer together," she said. "Now the manager hates the actor and the actor hates the manager. It wasn't so in olden times. A manager hadn't much money then and he took a chance and the actors were willing and glad to take a change with him because if he lost he lost as well as they. But the commercialism of today has ruined art and that's why I'm hoping the strike will mend our relations."

Dressler and Equity organizers knew that winning over the press would make or break the union, and the strike traded on the natural drama and talent of artists making their case. Dressler and the chorus workers garnered a ton of publicity marching in the street, but they did not stop there. Staging strike benefits would do more than gain attention; they would raise money. On August 18, at the first performance of several Equity would hold, Dressler and her chorus workers stole the show with a number called, "Our Chorus Girls."

Dressler led a huge group of chorus dancers onto the stage. One of the issues on the negotiating table was rehearsal; producers insisted on performers rehearsing for six to sixteen weeks – unpaid. Dressler reminded the room that she had been a chorus dancer at multiple phases of her career, and she was going to lead them now.

"Ladies and gentlemen," she said, "I can teach 200 chorus men and women a new set of steps in six to sixteen minutes." Along with a dance captain and rehearsal pianist, she did just that, and brought the house down, undermining producer insistence on the old way, and showing the crowd that these talented artists were more than just "chorus girls," but professionals doing what so many took for granted: using their skilled labor.

"It is madness to say that acting is not a trade," Dressler later said. "The production of anything necessary to the world is labor and must be learned."

Marie Dressler speaking to members of Chorus Equity during the 1919 strike.

At the end of August, Dressler served as the only female representation in Equity's delegation at a New York State Federation of Labor meeting in Syracuse, where the union's AFL affiliation became official.

Dressler called that event "the proudest moment of my life," nothing that she felt "a sense of oneness, of closeness to one's own people – the workers of the world."

Returning to New York City, Dressler continued to push as the strike wore on, to the dismay of employers. Reportedly, one even refused to go to bargaining sessions because she would be there. At the end of the month of striking, Dressler announced to the press that the strike was over: producers had agreed to terms in an indisputable victory for the workers. Unlike Actors' Equity, Chorus Equity established minimum wages in their ensuing contract: $30 a week on Broadway or $35 a week on the road. Dressler recalled that some "girls" had only been making $20 before.

Dressler's post-strike involvement in Chorus Equity was short lived. Although she was reelected in October, she became busy as she resumed her career with a self-produced revival of Tillie's Nightmare. In November, she resigned from her position in the union, and Blanche Ring, another star not actually performing chorus work, served after her. Around that same time, Dressler came under scrutiny when her company objected to not being paid for missed performances. She relented and paid her chorus, but she lost some of her hard-won good will as a champion of workers.

Dressler also later shared that she found the strike to be a great deal of fun:

"I jumped into the Equity scrap of 1919 on principle, as did many others, but it was more or less a merry war and everybody derived considerable amusement from it," she said. "It really was entertaining to see participants discussing their wrongs over a table at the Algonquin or the Ritz, and young women with charge accounts at well-known jewelers weeping into grape fruit [sic] supreme as they discussed their stage oppressors."

Marie Dressler with fellow performer Jane Miller at an event hosted by the American Woman's Association in 1900.

The strike was, by many accounts, an exciting time, as theatre workers came into their power and began to use their professional ability to lift spirits as a vital tool in the strike. But on some level, Dressler was disconnected from the very workers for whom she had fought so fiercely. Of course, not every actor lived a glamorous lifestyle, a stereotype that theatre workers still face when making a case for their place in the labor movement.

Dressler marched on, her career, finances and personal wellbeing continuing to encounter intense ups and downs. Unfortunately, her politics were also questionable. For one, she expressed early approval for Mussolini. And in the labor movement, she spoke out against Equity's (ultimately unsuccessful) attempts to unionize Hollywood.

"The theatre is organized now, and conditions complained of in 1919 have been changed and do not prevail in motion pictures," she said in 1929.

(Dressler was not the only star to turn on this effort; Ethel Barrymore, Equity's advocate in the 1919 strike, was instrumental in blocking that campaign.)

Dressler's career hit its critical peak with her Academy Award for Min and Bill in 1931, followed by another nomination the following year. By then, her health was failing, even as her stature as a celebrity stayed strong. For the last several days of her life, the New York Times ran regular articles updating readers about her health. She died on July 28, 1934, at the age of 65, of cancer. The Marie Dressler Foundation maintains her legacy, including awarding scholarships for Canadian students who are planning to pursue an education in the arts.

Wherever she went, Dressler was a force of nature. Her natural charisma and strong will perfectly combined to make her not only a successful actor, but an advocate for causes that stretched beyond her own self-interest. Her commitments to causes were intermittent, not lifelong projects, but she made them count. While she played a starring role in the 1919 strike, she knew the burgeoning movement was bigger than her. And while she was not at the forefront of feminism, she saw the ways labor intersected with gender and that women were workers equal in skill to men while also navigating unique vulnerabilities. Chorus Equity formally merged with Actors' Equity Association in 1955, and Dressler's impact remains present in the union today when theatre workers stand in solidarity to improve not only for their own circumstances, but to make better lives for their colleagues across the industry.